SCROVEGNI CHAPEL

DESCRIPTION OF THE FRESCOES CYCLE

Giotto’s fresco masterpiece at the Scrovegni Chapel is the world’s best preserved example of his work in this medium, as well as being the highest expression of his creative genius.

The cycle of works here provided a model that was innovative both in its account of pictorial space – the frescoes contain the first revolutionary uses of spatial perspective – and in its rendition of human emotions. It is also the only example of a fresco cycle that was a secular commission from an individual city burgher.

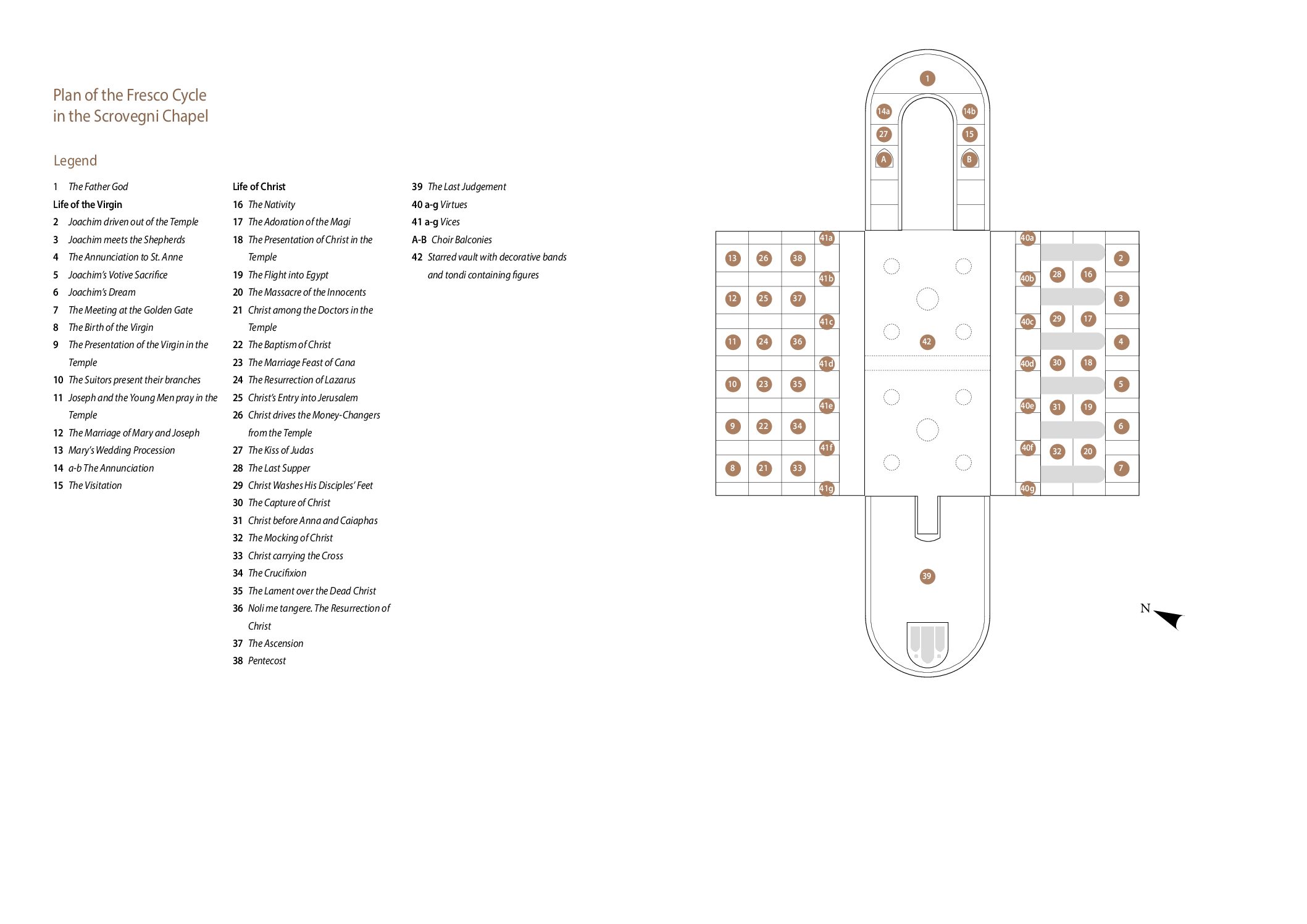

Extending over the entire wall space of the interior, the cycle – completed by Giotto at the beginnings of 1306 – comprises: 39 scenes from the Life of the Virgin and the Life of Christ, occupying the side walls and the arched space of the east wall; 14 figures depicting Vices and Virtues, along the dado of the side walls; two small choir balconies, painted to the sides of arched opening in east wall; and a majestic Last Judgement on the west wall.

The decorative scheme also includes the vault, which is painted with a star-strewn sky across which arch three decorative bands with 10, large and small, tondi containing figures.

The innovation in Giotto’s rendition of pictorial space is clear when one looks at how the gospel story unfolds along the walls, with each episode contained within a painted architectural framework.

The entire narrative is laid out over three levels, the story beginning in the south-east corner of the interior and then spiralling clockwise around the building; as one can see from the numbered sequence in the legend of the cycle, that narration also runs across the space of the wall at the east end of the nave. As for the dado, that too is divided into panels, with a narrative sequence that leads the faithful, both physically and spiritually, around to the Last Judgement depicted on the counter-facade of the west wall: following the Virtues, one comes to Paradise, depicted lower left; following the Vices one comes to Hell, depicted lower right.

Although the Last Judgement is not, like the other walls, divided by painted architectural features, it is still reveals a geometrical organisation of pictorial space.

On the areas of the nave’s east wall to either side of the arch opening through to the presbytery, Giotto painted two features that were totally new to the art of the day: the trompe-l’oeil architecture of two choir balconies (the so-called coretti). Empty rib-vaulted spaces which contain no figures, these allowed the artist to demonstrate to the full his skill in the rendering of three-dimensional space.

For the first time, the Florentine artist organised perspective space within a rationally conceived architectural framework, which defines and links the episodes in a narrative sequence. The overall layout also serves to establish parallels and correspondences between episodes in the Life of the Virgin and those in the Life of Christ that figure on opposite walls of the nave.

Another important feature to mention when describing the fresco cycle is the artist’s choice of palette. By opting for lighter and more luminous pastel colours, Giotto was able to achieve the gentle chromatic shifts that were very effective in creating the effect of natural light; even shadows, for example, are not rendered as patches of darkness but rather by muting colour tone.

The Scrovegni Chapel cycle was also innovative as an example of a new type of commission, from a secular figure who was not a ruling lord but a city burgher. The patron here was the banker Enrico Scrovegni; depicted in the Last Judgement below the figure of Christ, he is shown kneeling at the foot of the Cross in an act of devotion to the Madonna, to whom he is presenting a model of the chapel itself. The choice of scale here is another innovation: Scrovegni is not only depicted in Paradise, but he is also of the same size as the Madonna and the other saints, thus the ‘donor’ is no longer a marginal figure (as had been the case in the past) but takes on a central role in the scene depicted. And the significance of this is not restricted to the visual narrative: by having himself depicted within Paradise, Enrico Scrovegni wanted to portray himself as one of the Just, as a figure who could play a role in the city’s future fortunes. Scrovegni’s standing as new type of artistic patron is further underlined by the fact that there are two more depictions of him within the chapel: in a statue which shows him at prayer, and in the sculpted figure lying atop his funeral monument. Dating from between 1320 and 1336, these two works are attributed respectively to the sculptor Marco Romano and to the artist known as The Master of the Tomb of Bishop Castellano Salomone. As for the altar itself, this was sculpted by Giovanni Pisano, who signed the work, and was completed by 1305.

As already mentioned, the Scrovegni Chapel frescoes are also remarkable for the extraordinary realism with which they depict human emotions. Never before had painting so vividly captured the inner feelings of the figures portrayed.

In the Last Judgement the damned are depicted with terrifying realism as they are tortured by devils, the iconography being a visual exhortation to onlookers to mend their ways and follow the path of virtue. This realism can also be seen in the narrative that unfolds along the walls of the nave, for example, in the sheer intensity of emotion depicted in the Massacre of the Innocents.

This feature of Giotto’s work was already being cited by his contemporaries as a model to be followed; see, for example, the comments by Pietro d’Abano, a physician, philosopher and student of the stars who taught at the University of Padua and would, in 1306, inspire the iconography used in the astrological frescoes which Giotto painted in the Palazzo della Ragione (component part 2). A complement to this emotional realism was the fidelity with which the artist rendered everyday life, describing objects, fabrics and animals with such accuracy that one gets a vivid idea of life in fourteenth-century Italy.

Both secular and biblical figures are portrayed in what contemporaries would undoubtedly have recognised as the real world, and thus scholars credit Giotto with initiating that process which would ‘secularise’ the gospel narrative within a contemporary setting, a process that would then be further developed by other fresco cycles in fourteenth-century Padua, culminating in what one sees in the frescoes at the Oratory of St. Michael.

Within the presbytery of the Scrovegni Chapel there are two frescoes of The Madonna Suckling the Christ Child, both attributed to Giusto de’ Menabuoi, one of the other artists whose fresco cycles are included in the nomination (component parts 2-3).

The monochrome dado of faux marble exemplifies most clearly the origins of the technique used by Giotto in creating these frescoes. A development upon the ancient technique of wall-painting which Vitruvius himself had described in Book VII of his De Architectura, it demonstrates how Giotto breathed new life into an ancient technique, his innovations then being taken up and reworked by other artists in the city.